Introduction: My interest in this Israeli military action stems from my personal participation in it.

In 1959 I was enrolled for my compulsory national army service. This had been deferred until after I had completed my medical studies in Jerusalem and had graduated. In this way the army gained qualified doctors for two and a half years - at the derisory conscripts’ salary.

After a short course of military medicine, I was posted as Medical Officer to battalion 12 (‘barak’) of the Golani Brigade. I had become 214600 lieutenant doctor Yitzhak Loebl. My work consisted mainly of inspecting the camp's hygiene and sanitation and dealing with the young soldiers' fairly trivial routine medical complaints. After a year, I was promoted to become the Brigade Medical Officer, with the temporary rank of captain. It was 1962 and my army service was due to end some months later.

The following article was published 50 years later on 25.04.2012 in a special illustrated edition of the ‘Yediot Achronot’ newspaper. Ruth is a 'friend' of Alon, a kibbutz member of Ein Gev. She found the item in his Facebook and forwarded it to me. I translated it from Hebrew and added some more details from the web plus my explanations – [they are shown in brackets].

REVENGE, HEROISM AND FAILINGS ON THE KINNERET

JUBILEE OF THE ‘SNUNIT’ [SWALLOW] OPERATION

“The Syrians have been fishing in the Sea of Galilee” shouted the newspaper headlines of 11 March 1962. “The Syrians have continued their provocations in the Sea of Galilee. Syrian fishermen penetrated the lake’s waters at its north-eastern shore [in more than 10 boats] and fished [for over 4 hours] under the protection of the Syrian military positions. As before, the Syrians first fired on the Israeli fishing boats [using machine guns and recoil-less canons].

This further infringement of the cease-fire agreements between Israel and Syria was recorded in the operations diary in the office of the Chief of Staff. The clash about the sovereignty over the lake at the foot of the Golan Heights, which had been looming for a long time, was only a question of time.

|

| Yediot Achronot newspaper cutting of 11th March 1962 |

Signboard: Mitzpeh Nukeiv [View of Nukeib]. (Top left corner: the oak symbol of the Golani Brigade). Signboard: Mitzpeh Nukeiv [View of Nukeib]. (Top left corner: the oak symbol of the Golani Brigade). |

The green light was given on 15th March 1962, following the latest Syrian action. “This was again a planned Syrian provocation”, wrote Major Mordechai Shai, operations officer of the Northern Command, in his report to Meir Zorea, Commander of the northern sector – part of the file of the operation which has been disclosed courtesy of the military archive. “Immediately after the previous provocation the Syrians expected a response from us which seemed to them inevitable. We assume that they interpreted the absence of response as our weakness and allowed themselves repetitions of the provocation. If it were to be decided not to respond, the result would be the loss of our standing in this sector - in the eyes of our fishermen, and of the Syrians”.

That very night, the retaliatory action was on its way. Chief of staff Tzur handed the baton of command to the Golani [infantry] brigade, under the command of Motta [Mordechai] Gur. This was a precedent for the army – a large retaliatory action that was not allocated to a parachutist brigade. The target was the [Syrian] army post of Nukeib and the village of that name, overlooking the Sea of Galilee.

|

|  |

| Rehav’am Ze’evi (Gandhi) |

Arik Sharon (on the left) during a different Action |

Yaakov Dvir: not located to this day |

|

| Briefing before the action. The photographer received a medal |

|

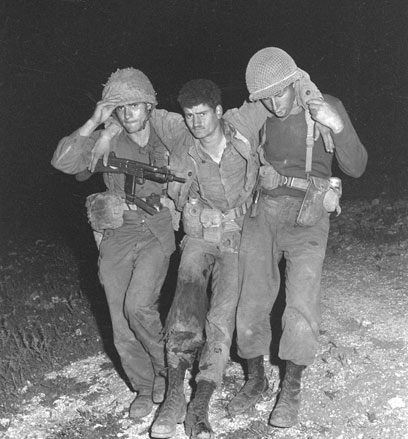

| Removal of an injured soldier during the battle |

From the very first minute, the intended clean surgical reprisal turned into a noisy clash, under heavy fire from fortified Syrian forces. Although the Nukeib action was recorded in the annals as a success - Golani had accomplished the goals that it had been set and proved that human resolve can be almost limitless - the price in blood was heavy. Seven fighters were killed and another is still listed as ‘missing’.

“Very quickly the business became complicated”, remembers former major-general Shlomo Gazit, who was the deputy commander of the Golani brigade at the time. “We had no element of surprise at all. The fighters did perform their task – the position was destroyed. But from a national point of view, such an action, at such a price, was not justified in those circumstances”.

The armistice agreement determined that the border between Israel and Syria should run at a distance of 10 meters east of the Kinneret and that the Syrians should have no fishing rights. But the rich fish stocks, at the estuaries of brooks flowing into the lake and the pumping installation, induced Syrian fishermen, backed by their army, to violate the agreement – to cast nets and “to paddle” in the lake. Israeli protection boats patrolled to prevent this and removed the Syrian’s fishing nets. The Syrian army, thanks to their topographic advantage, repeatedly attacked the Tiberias fishermen and fired on the Israeli protection boats from their positions at Nukeib and Kursi.

[Israel was at a double disadvantage as a result of the 1948-9 armistice agreement with Syria: Not only did the Syrians on the Golan heights have a clear view (and easy range) of the Israelis fishing in the lake, but the territory east of the lake was demilitarized and out of bounds for the Israeli military.]

Historical research points to another Syrian motive for breaking the armistice agreement – the political instability in Syria following their military coup, and their struggle vis-à-vis Nasser’s Egypt. In those years Syria and Iraq were conducting negotiations for contracting a military pact. The increasing Syrian confidence in their national power and their realisation that a firm line against Israel would assist their internal stability – all these motivated the Syrians to seek an escalation of the hostilities - and to be prepared to pay the price.

To break the monopoly of the parachutists

March 1962 was the climax. After the firing on the Israeli protection boats on the 15th, despite Israel’s sharp warnings, it was clear to the area military staff that the telephone call [from the ministry of defence] might come any minute – and it did. Operation “Snunit” to conquer and destroy the positions of Nukeib and Kursi was launched. Motta Gur had been appointed as the commander of the Golani brigade exactly for just events. Until then it had been customary for reprisal actions to be carried out by the parachutists’ brigade. When Ben Gurion asked the Golani and the parachute brigades how long each would need [to prepare] for such an action, Gur answered enthusiastically “today”. The parachutists would have needed four days. Thus, recount the fighters of that event, the die was cast – the operation was Golani’s.

|

| "There was no time for preparations" |

# Force A under the command of Tzvika Offer, the head of the Golani special reconnaissance unit, was responsible for occupying the Nukeib position and blowing it up.

# Force B, which included a unit from the school of commanders under the command of Beni Inbar, the school’s commanding officer, was responsible for occupying and purging the village, and also demolishing the observation post to the south of it.

# Force C under Uri Shilo, the commander of battalion 51, would be a reserve force, riding on ten half-tracks, for use as an extraction unit or to assist the fighters.

# Forces D and E, part of them recruits who had been in the army four months at that point, under Yehuda Gavish the commander of battalion 13 and his deputy Moshe Gat, were responsible for isolating the battle zone and blocking and removing any Syrian reinforcements.

# Force F, the mortars regiment 334, will wait in Ein Gev for development.

# Avraham Vered, a photographer of ‘Bamachaneh’ [the official army journal] also joined the force.

The naval force consisted of 20 fighting men. They were meant to occupy the Kursi position. But the higher command expressed their reservations about the task, fearing an early detection that would neutralize the element of surprise. That night there was a full moon illuminating the lake. “The navy on the eve of the action raised doubts about the possibility of executing the action” said Yitzhak Rabin, head of operations and the deputy chief of staff, at the investigation that took place a few days after the action. “But on the day, they still rolled the matter forward”. The air force also had their reservations, based on the meteorological forecast of clouds that would hinder their ability to back up the fighters.

The plan had been submitted to the minister of defence (Ben Gurion) weeks before, but the details of the action were kept secret until the very day. The forces were briefed on the ground, but most had little time to study the task and all its components. “The forces set out to the area with the units of Tzvika [Ofer] and Beni [Inbar] knowing what they had to do. The commanders’ knowledge of the area was not bad, but that of unit A was ‘so – so’,” said Gur at the investigation. “There was no time for preparations”, says today Ya’akov Even, the deputy commander of Force B.

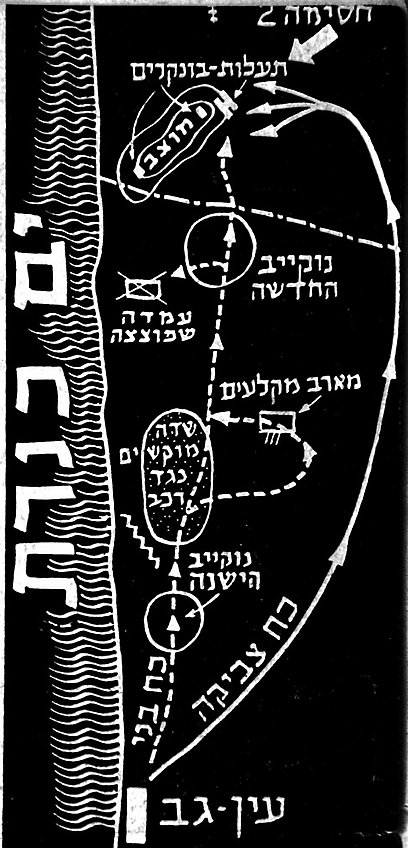

|

Sketch map of the action. 'Blocking force 2'. Trenches - bunkers. The army post. New Nukeib village. Position that was blown up. Machine gun ambush. Anti-vehicle minefield. Old Nukeib village. The routes taken by the forces Beni (dashes left) and Tzvika (solid curved) At the bottom – northern building of Ein Gev. |

The intelligence collected towards the action missed something else – information that turned out to be critical for the action from the moment that it began to get complicated: [It was not realized, nor investigated] that the Syrian forces were well prepared [and alert], as a result of their assumption that Israel would have to respond. The enemy forces turned out to be larger and much more determined than the Israelis expected. The Syrian soldiers demonstrated stubborn resistance. The element of surprise was totally absent.

According to the brigade’s operations diary, which was on file in the archive, the forces received confirmation at 21.25 and started to move. Force B under Inbar marched first, climbing the slopes towards the village of Nukeib. Already along the way the force encountered firing from a position in the village. The surprise vanished. Yaakov Even, Inbar’s deputy, was sent to clear that position, and simultaneously the force of Inbar began its assault. A group of Syrians soldiers started to run away, and not before they had managed to warn the adjacent position.

|

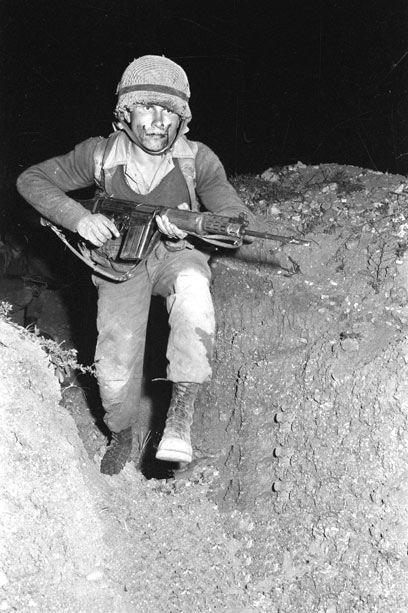

| "All the trenches opened fire" |

“They were waiting for us”, remembers Zeev Kishon, a fighter in Force A. “We lost the element of surprise when we encountered an ambush on the way to the army position. From that instant the entire sector woke up. The civilians who started to escape separated us from the target and there was nothing we could do. We were instructed by radio not to shoot until the last civilian had passed. That gave the army post more time to get organize and to wake the entire sector”.

When the commander falls to the ground

At that moment the post opens heavy fire on the force of Ofer. “All the trenches began shooting, including tracer bullets. With the first shots I sustained an injured commander. The fighters were shocked when they saw their commander fall to the ground. Ofer the commander grasped the situation immediately and before the soldiers could develop paralyzing shock, he ordered an assault. As he led his force towards the post, they mingled with the crowd of civilians who were escaping from the village.

Ofer and his men reached the trenches of the post. They discovered that the Syrian positions were well fortified and the enemy number was greater than they had expected. Whoever stepped forward was hit by the gunfire. Each bend in the trench required its own battle. [Ofer’s men had insufficient magazines [five each] and grenades. Ammunition was passed forward along the trench to the active fighters. And they also used the weapons of the dead Syrians.]

At 23.21, according to the action diary, Ofer called for help and requested the extraction of a wounded soldier. “I am subjected to strong fire”, he reported to the command in Ein Gev. “I cannot outflank on the right. Stubborn fighting in the trenches, from the direction of the village. I am being fired on, I have many wounded”.

“Are you continuing” Ofer is asked. “Yes, continuing” he replies.

“Beni cannot help yet, but he will soon”, the command replied.

A minute later, at 23.22, the command instructs Force C (the half-tracks) to move and help to occupy the army post. [Only nine half-tracks had reached Ein Gev in time, and one later shed its track]. Commanded by Uri Shilo, force C left Ein Gev. On their way [north] they crossed the bean field that separated the kibbutz from Nukeib. That revealed the mistake – one half-track struck a mine. Very quickly the force realizes that they were caught in a Syrian minefield. Due to the urgency of the action, no mine clearing personnel had been included. The half-track of the commander Shilo also struck a mine, he was injured and lost his hearing. “I told my commander that we shall enter some 70 to 80 meters and skirt around it” Shilo’s deputy said at the de-briefing. “I reckoned that we might have to throw some stones [to trigger the mines?]; but while I was still considering, we struck a second mine”. The help force itself now required help and extraction by the civilian tractors of Kibbutz Ein Gev, [and Ha’on and Tel Katzir. One of the tractors also struck a mine].

‘Mivza Arnevet’

Simultaneously, the fighters of Flotilla 13 were on their way across the Kinneret from Ginossar [kibbutz on the western shore of the lake, opposite Ein Gev] to Kursi. “During the last briefing - reported the navy commander Yochai Bin Nun at the de-briefing, “I received a phone call from the regional commander that the [infantry] force had encountered an ambush and therefore the element of surprise will not have a big chance”. The moon shining on the sea rendered the fighters particularly exposed. “The Kinneret was like a shining mirror”, Gazit remembers, “the Syrians saw everything”.

When the fighters neared the shore, the Syrians fired two coloured rockets. Still, the swimmers were instructed to enter the water. “Confirmation for immersion arrived” related the flotilla commander Shapira. Then shooting began towards the fighters, and the factor of surprise was lost. The naval action was cancelled before it had even begun. Under fire, the fighters returned to their boats and left the area. [This episode was later called unkindly in navy circles the ‘rabbit operation’ – Mivza Arnevet].

Extraction of the half-tracks from the minefield – from the de-briefing recordings

Force B commanded by Inbar completed the clearing of Nukeib village after a bitter battle. When Inbar heard of the trapped half-tracks, he suggested to Motta Gur that he combine with force A, under the command of Ofer, and overpower the post where exchanges of heavy firing were taking place. In the fog of the battle, when it seemed that everything was being disrupted, the resourcefulness of Inbar and Ofer brought the task to its successful completion in the end. While they were on the move, they modified the task, and fixed a common boundary for their actions to avoid mutual shooting. Inbar’s deputy, Even, told the de-briefing: “I got to the edge of the trench of the post. Five or six soldiers lay [at the bottom] on their sides with their weapons pointing upward and whenever we advanced they covered us with a salvo. I felt a rustling near my ear. I pulled the safety pin and waited until there was only a second to the explosion”.

The overpowering of the Nukeib army post - from the de-briefing recordings

The Nukeib post was occupied and blown up. The fighters then made their difficult way out. In the absence of the half-tracks, which were stuck in the mine field, the wounded were evacuated carried on stretchers – all under an artillery barrage that constantly ranged and pin-pointed the fighters. [As the soldiers moved towards Ein Gev,] the shelling advanced towards the kibbutz and the heavy bombardment also hit other settlements in the region. [Some 2,000 shells were fired by the Syrians during the action.] The command wanted to launch the air force to silence the shelling, [and 3 (or 5) Vaotour aircraft* were launched. Two batteries of 120 mm mortars were also used.] But dense clouds interfered with the accuracy of both the aircraft and the artillery.

[*Sud Aviation – French. Israel was their only foreign customer. They purchased 28, withdrawn in 1973.]

The evacuation back to Israel took a long time. Half-tracks that could not be extracted were stripped of their weapons and blown up, but four were salvaged by the Syrians and exhibited as loot in Damascus.

At 05.25 the operations officer reported that “Beni and Yossi have passed Congo” – the code for Ein Gev. The action was complete.

Where is Ya’akov?

In Ein Gev the work of treating the 43 wounded was progressing. Also at that point the number killed was established. Six soldiers were dead – and two were missing. After a few days it became known that one body had been found by the Syrians, and some days later the body was returned in exchange for the single Syrian prisoner who had been captured during the action, But the second missing soldier, Ya’akov Dvir [Ravkind] from Petach Tikva, has not been located to this day.

| The report about the missing soldier |

|

| The memorial to the missing soldier Ya’akov Dvir |

“The searches continued all the time”, said Dvir’s sister, Yochi Eisenberg. “They tried to find the beginning of a thread but they did not succeed. Even today they are still searching, but until now we know nothing”.

Later, in December 1968, one of the heroes of the action, Tzvika Ofer, was killed during an exchange of fire with marauders in Wadi Quelt.

“An orgasm of an assault”

On the day following the action, the prime minister and minister of defence David Ben Gurion got to Yavne’el, met the fighters and congratulated them on completing the task. On that very day, incidentally, the Syrians fired towards the Kinneret, before relative quiet prevailed. The newspapers reported an impressive operational success. The number of casualties and injured on our side was concealed. Radio Damascus, on the other hand, reported that about 200 Israeli soldiers had been killed and much plunder had been found in the area. It was the BBC that discovered contradictions in the Syrian reports. Some 40 Syrian soldiers had been killed and some of their bodies were exhibited as dead Israelis.

|

Ben Gurion visits the fighters at Yavne'el the following day |

The De-Briefing

On 26th March the general staff forum was convened to investigate the action and to discuss the failings that were found. The discussion was opened by major-general Yitzhak Rabin. “The Israel army is strong and good”, he said, “the achievements of the ‘Snunit’ action are great and numerous. I think that we need to have sufficient courage to define the faults that have been revealed in the preparations for the action and in its execution”.

Each of those who participated in a command role in the battle presented his actions during the combat. Much praise was given by the generals to Tzvika Ofer, who had led the assault on the syrian post while under fire – just as the force was absorbing a volley of shots and its fighters were being hit.

After the fighters had presented their descriptions of the battle, general Ariel Sharon requested leave to speak. Sharon, the acknowledged ‘father’ of the parachutists’ retaliatory actions, wished to cool the enthusiasm a little.

“I had the opportunity on Friday, in common with a large part of the audience here, to know that there was going to be an action. I exploited my authority and entered the operations centre, where I could follow the course of the battle” began Arik – at the time a brigade commander who was not associated with the ‘snunit’ action. “This is an achievement for the signals setup, that one can follow events right into the bunker. One can hear the breathing of the fighters.

I do not wish to talk and deal with the topic of the fighting, I think that this makes no difference. The unit has good commanders and trained soldiers. They did assault - it is a fact that they assaulted. I don’t know if I should use the term ‘Orgasm of assault’. We were all excited by the fact that the soldiers had assaulted – but we are not in the year ‘52 but in ‘62 and there is no reason for the soldiers not to assault. We are full of admiration but there is no reason to exaggerate – they did exactly what they were trained for years to do.”

Sharon also did not spare those who had determined the targets of the action. “I think that we demonstrated a total lack of imagination regarding the topic of the targets. If one wishes to cause casualties, then to tackle an army position is not the right thing. Either the enemy force escapes and then you do not cause losses, or they fight and possess all the elements of combat and of inflicting losses. In practice the losses will then be balanced. It is worth demonstrating more imagination and not adhering to routine actions”.

|

| The fog of battle. "There was really no surprise". |

General Rehav’am Ze’evi [‘Gandhi’], chief of staff of the central command, criticized the surgical method that the armed forces use, of a measured penalty directed only at the post’s soldiers. “There was once a chief of staff who said that every attack on the border has to be totally destroyed. It seems to me that this motto has not lost its relevance. If [the destruction of] Nukeib is wanted, it has to be done with threshing sledges. It could be done by the air force. The aim at Nukeib was not only to enhance the image [?] of the defence forces. The main aim was to emerge victorious.

Gandhi also criticized the way that the number of Israeli casualties was concealed in the media. “When they say within the defence forces that there are 40 injured whereas in the newspapers they reported 10, that will result in the army not understanding how many there really are. The difference between us and the Arabs is that we publish the truth. We must not be allowed to create a policy of false publications.

[Later, In 2001, while he served as a government minister, Gandhi was assassinated by 4 Arabs at the Hyatt hotel].

The chief of staff Zvi Tzur wound up the discussion and replied critically to the words of Sharon. “After the deed, everybody is clever. I did hear those who had imagination. There was one possibility, with much imagination, to take a unit of 15 men, move them by air to the Syrian lines and to establish [?] artillery targets. I am not sure whether we would have succeeded.” With regard to the compliments lavished on the assault Tzur said: “I do not understand why one should not get excited? It is a seal of honour for Golani. But I’m sure that the paratroops can also do it, and we also have other units. We should be proud”.

“We marched with our head into a wall”

|

| Memorial ceremony above the Kinneret [March 2012] |

In retrospect, we should have delayed. That method of an immediate strike was shown to be a mistake – it would have been better had we waited for optimal conditions”.

“We did not lose the element of surprise - because from its onset the action did not include such an element” – Ya'akov Even is certain. “The Syrians knew that the blow will come and it will come in the area of the Kinneret. If not tomorrow then the day after. We marched with our head into a wall, and went to fight without any surprise; and we paid a heavy price for completing the task. That was a mistake”.

Walter’s Additional Information

[I copy here parts of my blog from 2008].

In March 1962 the Israel government decided to attack and demolish the Syrian position. The task was given to the Golani Infantry Brigade, in which I served at the time as the Brigade Medical Officer. So I was put in charge of the casualty clearing station for the action.

As the brigade medical officer, I had been able to attend the weekly medical rounds at the Rambam hospital in Haifa. But just as I was scheduled to present a case at the next meeting, I was told to cancel my visit - without revealing the planned action at Nukeib, of course.

On Friday 16th March 1962 all the infantry units reached kibbutz Ein Gev under cover of darkness. I was met by my cousin Reuven, a veteran of the kibbutz, who was in charge of local security. He suggested that I set up my clearing station in one of their underground shelters. But I decided on a location with easy access from the battle area and for medical evacuation, in an open yard just inside the kibbutz gate.

Later an enclosure for ostriches stood on that spot. We erected the tent for receiving casualties and by the light of the incandescent kerosene lantern we prepared our medical equipment, assembled some intravenous drip sets - and waited.

When the attack on Nukeib started, the Syrian artillery on the Golan ridge above began an intensive shelling of the area. Some of the shells exploded in the kibbutz yard, quite near to our tent. Several shrapnel fragments actually penetrated the tent’s canvass, but nobody was hit.

Before long, casualties from the battlefield began to arrive. Ignoring the continuously exploding shells around us, we examined and treated the injured, completed their documentation and arranged their ambulance transport around the lake to Poriya hospital. Several soldiers were dead on arrival at my tent. I cannot now recall the numbers - but later I ascertained that all 30 casualties who had arrived alive at my clearing station also reached the hospital alive.

One of the dressers in my team had forgotten his steel helmet in camp. I found it most cumbersome to perform my work while wearing my helmet. So I gave it to him. One of my Battalion Medical Officers actually did sustain a penetrating head injury - despite wearing his helmet. Luckily Yochanan later made a full recovery.

After some hours, the stream of the casualties ceased and I assumed that the fighting was over. But the field telephone wires to the command post had been cut by the shells, despite being repaired twice. Dawn was breaking, but the Syrian shelling was still going on. Thanks to my previous visits to Ein Gev, I was the only person in my tent who knew where the shelter with the command post was located. So I retrieved my helmet and ran there across the kibbutz to ask for instructions. They had forgotten about my medical clearing station. “Of course”, I was told, “dismantle your tent and withdraw to the force's assembly area in the Yavne'el Valley, across Lake Tiberias”.

When we got there, I lay down in one of the ambulances and promptly fell asleep. As a result, I missed the visits by David Ben Gurion the Prime Minister and by the Chief of Staff Zvi Tzur. In the afternoon we returned to our camps and I was given home leave. For the following few weeks, whenever a door was slammed loudly, it made me start and duck instinctively.

The next morning two Army reporters arrived at our flat in Jerusalem. They said that I had been recommended for mention in dispatches by the Chief of the General Staff and they required photos. I regarded myself as primarily a doctor, not a soldier. So I was photographed wearing a civilian shirt and tie.

During the next Independence Day celebrations, I attended President Yitzhak Ben Zvi's customary reception to honour soldiers who had been mentioned in despatches. As usual, this was not followed by any sort of party.

Some months later I was demobilized. I moved to London for postgraduate medical training. The specialty of rheumatology was not well developed in Israel at that time. Ten years later the Israel embassy unexpectedly phoned us one day. We were told that according to an Act passed in the Knesset in 1973, I was entitled to receive the Israel ‘Medal of Courage’. [There is one higher grade medal – the medal of bravery, in which some of its recipients actually died during their action.] The medal of valour is awarded 'for an act of gallantry, at the risk of life, during fulfilment of combat duty'. It may be worn on independence day, but the red bar may be worn at any time. Until then, during the first 34 years of Israel's existence, it had been awarded to only 220 soldiers.

So my wife Judith and I were invited to the embassy. There, an official made a speech, and handed me the medal in its olive wood case [see photo] and a certificate. No hospitality was provided. I had not experienced any fear during that night's shelling and I did not regard myself as being particularly brave. Had I taken part in this action as a combat officer, instead of as a doctor, my conduct might not have been regarded as all that outstanding. I have never worn the medal, nor had I told any of our friends about it.

To my knowledge, I only derived benefit from this honour on one occasion, when I applied for a medical post at Bethnal Green hospital. During the interview one of the consultants seemed particularly interested in my award. I was appointed to that post, and later I discovered that Dr Ian Gilliland was a staunch supporter of Israel. He had previously been a volunteer on Yigael Yadin's excavations at Masada.

Post Script

Recently, when I decided to write this blog [in 2008], I could not remember the number of casualties that had passed through our casualty clearance tent. I thought that perhaps Dr Eliyahu Gillon, who had been at the time the Commander of the Army Medical Corps and my professional superior, might be able to obtain access to the relevant archive. I managed to ascertain his address from a mutual acquaintance: he was retired but still doing research at Tel Hashomer hospital. I wrote him a friendly letter asking for his help. I never received a reply. Many Israelis are well known for their reluctance to write letters.

So I was prepared to skip the casualty figures, but I contacted the Public Relations Section of the Israel Embassy in London. I wished to ensure that my description was no longer classified; and incidentally, could they possibly obtain the casualty data that I was seeking. They replied promptly and assured me, that they did not 'censor' such texts as my memoir. As to the number of casualties - that would be very difficult or impossible to ascertain at this time.

Like Baldrick (of television notoriety), this gave me the idea for a cunning plan: One of my relatives in Ein Gev is a qualified midwife, who had worked for many years at Poriya Hospital. Perhaps she would be able to obtain the information from the records of her hospital's casualty department? I knew that all the injured had been evacuated to Poriya during that one night, of 16 - 17 March 1962. Within a fortnight she e-mailed me the answer that she had received from the archive: there had been thirty casualties, including two shell-shocked. So now I could write my blog.

Motta Gur

I liked Motta Gur, the brigade commander. He was clearly intelligent, competent and kind. The newspaper article that I translated above diminishes his achievement in the ‘Snunit’ action. But this is written 50 years after the event.

I liked Motta Gur, the brigade commander. He was clearly intelligent, competent and kind. The newspaper article that I translated above diminishes his achievement in the ‘Snunit’ action. But this is written 50 years after the event. In any case, Gur’s career continued successfully.

He was chief of Staff from 1974 to 1978; and in 1981 he was elected to the Knesset. Later I heard that in 1995 he had developed widespread cancer. One evening he went into his garden in Tel Aviv and shot himself. He was 65, married, with 4 children. He was honoured with a military funeral.

Towards my discharge in 1962, I assessed my future prospects. Medical employment in Israel was uncertain: the country had one of the highest ratios of doctors to the population. Israel’s socialist government had created a perverse medical salary structure: low wages were boosted by generous artificial ‘extras’. But these supplements ceased at retirement, resulting in a derisory pension. Later I heard of senior surgeons who still had to augment their income by rotas in the casualty room. As an ‘army reservist’, I was liable for annual compulsory military service to the age 50. That would swallow up my leave, again at very inadequate wages. For any travel abroad I would have to get permission from the army, and also to pay the exit travel tax. So I decided to leave Israel. Judith and I moved to England, where Judith had relatives.

I arranged my British medical registration and looked for medical employment. I also signed on at the Israel embassy – I was still an Israeli army reservist. However, after the ceremonial award of my medal, when the embassy obviously knew my whereabouts, they never contacted me again. I was not invited to Independence Day celebrations, or notified of any other events. I suspect that in their chauvinistic arrogance they regarded me as a 'Yored', an emigrant from Israel and therefore a renegade - practically a traitor.

For example, shortly after I had left Israel, a friend described to me his guided tour of Jerusalem’s Talbiyeh quarter. When the group passed our former house at 20 Balfour street, the official guide mentioned that I had lived there, having being mentioned in despatches by the chief of staff – ‘‘and now he is a doctor in Dimona’’. The Israeli nuclear reactor is located there. That was a remote and highly secure location in the Negev, where nobody would be able to locate me. This concealed the fact of my unpatriotic emigration.

The Yediot Achronot feature that instigated my present work on this subject, and the creation of this blog, was published for the 50th anniversary of the ‘Snunit’ action. It reports the reunion of the participants in March 2012 near the original location of Nukeib, just north of Ein Gev – photo above. I knew nothing about all this until Ruth sent me the newspaper article. Clearly the organizing authorities had decided not to invite me or even to inform me. But by then I was a permanent resident in Britain, and no longer even an Israeli citizen…

28th July 2012